Author: Iron Pillar Brother in CRYPTO

Many years from now, facing the newly appointed Kevin Warsh and the continuous public pressure from Trump, Powell might recall the morning he first walked into the Federal Reserve Chairman's office.

It was an era where everything still seemed controllable, even though the world's rightward turn was already inevitable.

At the time, the 64-year-old Powell did not know that he was about to become the longest-serving Fed Chair in history to operate in an abnormal state: he would face the pandemic, unprecedented fiscal expansion, runaway inflation, asset bubbles, and geopolitical fractures. He would also be forced, time and again during crises, to push the Fed into the spotlight.

I. Redefining the Fed: Farewell to Backstopping—Dovish or Hawkish?

For a long time, the Fed was no longer just a central bank. It became the buyer of last resort for markets, a shadow ally of fiscal policy, the lender of last resort for banks, and the ultimate backstop.

And Powell, gradually, was shaped by circumstances from a technocrat known for his steadiness and skill in managing expectations into the guardian of this vast and bloated system.

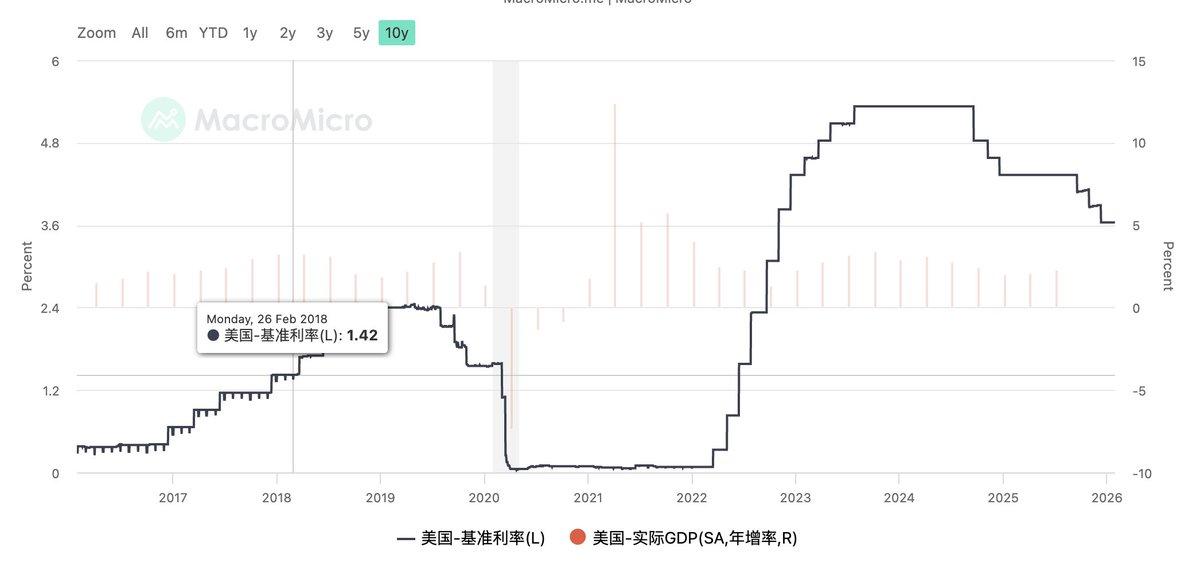

The起伏 (fluctuations) of interest rates during Powell's 8-year tenure

Until today.

As Kevin Warsh's name emerges as the next Fed Chair, what is truly changing is not merely a label of hawk or dove, but a redefinition of the Fed's role for a new era.

Warsh is not a traditional hawk obsessed with balance sheet reduction, nor a dove who only knows how to cut rates to nurture markets, nor simply an anti-establishment figure.

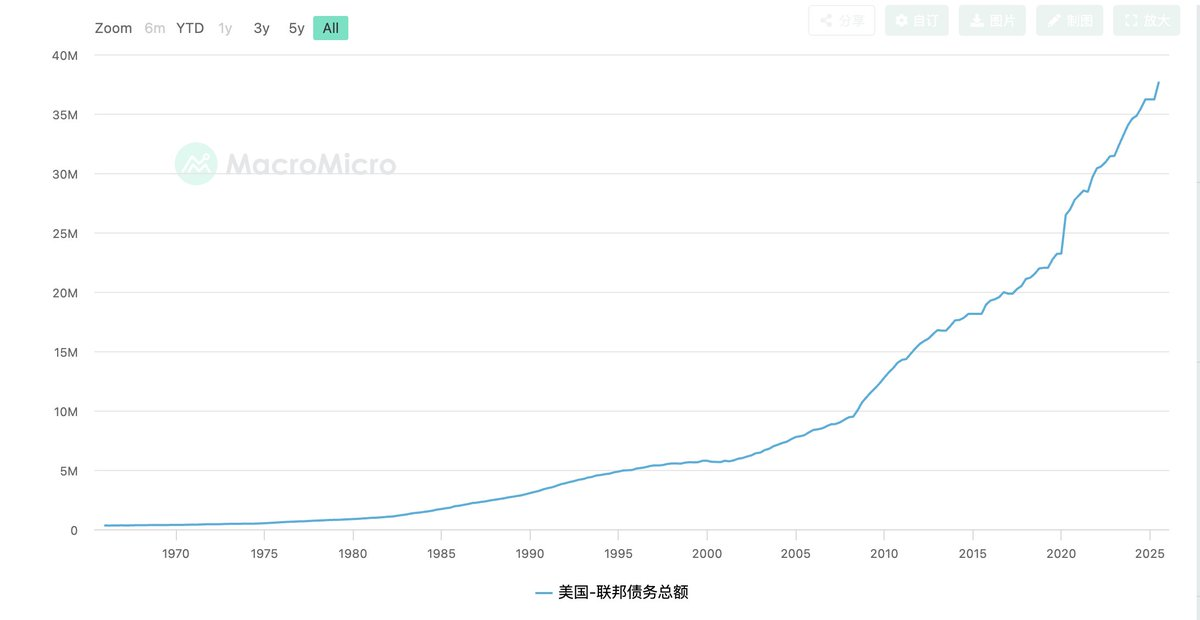

What he truly represents is an answer that the Fed of the new era must provide against a backdrop of growing market skepticism about the sustainability of the massive national debt: should the Fed continue to bear the responsibility of backstopping all debt problems?

In Warsh's proposals, he repeatedly mentions thorough reform—not just changes in the rate path or adjustments to the balance sheet size, but a systematic reflection on the logic of monetary policy over the past fifteen years. This extreme form of distorted Keynesianism is coming to an end.

The history centered on demand management, using asset price prosperity to mask productivity stagnation, has reached a dead end.

For Trump, Warsh is a controllable reformer: willing to cut rates, understanding debt realities, and unlike Hassett, not carrying strong political baggage, thus maintaining the necessary independence and dignity of the central bank.

For Wall Street, Warsh is a rule-abider: emphasizing monetary and fiscal discipline, opposing unconditional QE, and preferring institutional adjustments over monetary policy interventions to manage markets.

As mentioned previously in a shared space, perhaps the Fed Put will cease to exist in the next four years. It may be replaced by a more restrained central bank, clearer boundaries of responsibility, and more frequent, yet more genuine, market fluctuations. This will bring an uncomfortable adjustment period for all market participants.

II. The Gravitational Field of Reality: How Long Until a True Return, and Is It Even Possible?

Before Warsh takes office, the prevailing mood is pessimistic. After all, according to Warsh's philosophy, there should be significant balance sheet reduction and a strong fight against inflation.

However, the current U.S. economy is in a state of fragility yet极度依赖 (heavily reliant on) a stable narrative: fiscal deficits are high, debt interest payments are nearing the brink of失控 (being out of control), real estate and medium-to-long-term financing are highly dependent on long-term rates, and capital markets are accustomed to policy backstopping.

What Warsh advocates—rate cuts + balance sheet reduction + a smaller central bank—means: it requires fiscal policy to重新面对成本 (face costs again) and exercise discipline; it requires markets to独自承担风险 (bear risks alone); and it requires the Fed to relinquish the backstopping power accumulated over the past fifteen years.

This path is not impossible; it makes logical sense and aligns with common sense. But realistically, the margin for error left for Warsh is not large, and it highly tests his control over the pace.

If balance sheet reduction pushes up term premiums, raising medium-to-long-term rates, thereby suppressing housing, investment, and employment;

If markets experience剧烈波动 (violent fluctuations) during the process of the central bank no longer backstopping;

If voters feel the real costs brought by this so-called return to discipline.

Political pressure on the Fed will quickly revert to the familiar direction: stop balance sheet reduction, slow down reforms, prioritize stabilizing growth.

Over the years, both voters and capital markets have developed a strong path dependency through repeated crises. This inertia cannot be彻底打破 (completely broken) by a single personnel change.

A more realistic assessment is: Warsh may push for a change in direction, but a true return is unlikely to happen in one step.

III. From Trump's Perspective: Another Solution Behind Warsh's Appointment

As is well known, Trump has always needed low interest rates.

But at the same time, early in his term, he flamboyantly adopted Musk-style efficiency reforms, attempting to drastically cut government spending and reshape fiscal discipline. These two goals—low rates and spending cuts—are inherently conflicting within the traditional framework.

Thus, a more interesting question arises: if Trump is unwilling to fully rely on a dovish central bank backstop, yet is aware that fiscal conditions are nearing失控边缘 (the edge of being out of control), then is choosing Warsh itself a non-traditional solution?

At this stage, the U.S. fiscal deficit rate and debt scale are approaching a critical inflection point. Continuing down the dovish path of the past fifteen years—more aggressive rate cuts, more direct central bank intervention, blurrier monetary and fiscal boundaries—might seem to buy短暂稳定 (brief stability), but in reality, it continuously透支 (overdraws) dollar credibility and exacerbates inflation problems.

The political comfort period for this path is very short, and the probability of failure is extremely high. Once inflation rebounds and long-term rates spiral out of control, the responsibility will almost certainly fall back on the White House itself.

We must always understand: Trump is, from start to finish, a master of passing the buck. And Warsh's value lies precisely not in his apparent difficulty to use, but in the ability to use Warsh's hand to pressure Congress.

If the Fed, under Warsh's leadership, clearly refuses to continue backstopping fiscal policy and refuses to unconditionally suppress term premiums, then rising interest rates, exposed financing costs, and显性化 (becoming apparent) fiscal pressure will no longer be the direct consequence of political decisions, but the natural outcome of market discipline.

What would this lead to? For Congress, continuing unconstrained spending expansion would quickly become unsustainable; for the fiscal system, cutting welfare and compressing deep budgets would, for the first time, have a被迫发生的 (forced)现实基础 (realistic basis); instead of relying on Musk-style plugging of leaks.

Even if this path fails, even if market reactions are excessive and the reform pace is forced to slow, Warsh remains a perfect scapegoat.

Or, Warsh doesn't even need the reform to succeed; he just needs to fully expose the problems to change the current state of博弈 (game theory) between Trump, Congress, and the Democrats.

This, perhaps, is the most realistic, and also most brutal, political significance of Warsh's appointment.

IV. Facing the Future of Debt: Buying Time, No One-Size-Fits-All Solution

Pulling the perspective even higher, one finds that both Warsh's reform vision and Trump's political布局 (layout) cannot escape the same现实约束 (realistic constraint): the U.S. has entered a debt-dominated era.

The scale of debt dictates a brutal fact: the U.S. no longer has the policy freedom for thorough correction,只剩下 (only left with) choices of how to delay and how to转移 (transfer/shift).

This is why buying time has become the only feasible, yet least dignified, path. Rate cuts use future inflation risk to alleviate current interest pressure; balance sheet reduction attempts to use institutional discipline to修复 (repair) central bank credibility; fiscal reform uses political conflict and electoral costs to temporarily smooth the debt curve.

But these choices conflict with and constrain each other; none can form a complete闭环 (closed loop) independently.

What Warsh truly faces is not the question of whether to reform, but:

In a highly financialized, politically polarized, debt-inflated system, how much real cost can reform bear (withstand)?

From this angle, no matter who comes up, they cannot provide a one-size-fits-all solution.

This also means that in the next four years, what markets need to adapt to is not a single policy shift, but a longer-term, more反复的 (repetitive/volatile) state. Interest rates will not return to the zero comfort zone, but也难以长期维持高位 (will also find it difficult to maintain high levels long-term); the central bank will not backstop unconditionally, but也不可能真正放手不管 (cannot truly let go completely either; crises will not be彻底避免 (completely avoided), only postponed and拆分 (broken down).

In such a world, macroeconomic policy no longer solves problems; it only manages them.

And this, perhaps, is the final point for understanding Kevin Warsh and Trump's布局 (layout): they are not competing for a better answer, but in an era without good answers, fighting over who decides how the costs of the past are allocated now.

This is not a story about prosperity.

It is merely the beginning of an era where reality, debt, and supply constraints become apparent again.